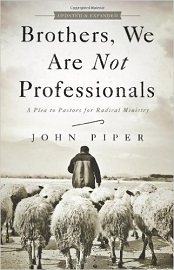

This book is a revision of a volume by the same title published in 2003. The updated edition includes six new chapters.

This book is a revision of a volume by the same title published in 2003. The updated edition includes six new chapters.

Brothers, We Are Not Professionals caught my attention with its title. Piper explains the title in the preface to the new edition. He contends that there’s a “quiet pressure felt by many pastors” to “be as good as the professional media folks, especially the cool anti-heroes and the most subtle comedians.” He continues, “This professionalism is not learned in pursuing an MBA but in being in the know about the ever-changing entertainment and media world. This is the professionalism of ambience, and tone, and idiom, and timing, and banter.” After a lengthy list of the activities in a pastor’s life, including prayer, trusting God’s promises, and pleading with backsliders, he asks, “Why do we choke on the word professionalism in those connections? Because professionalism carries the connotation of an education, a set of skills, and a set of guild-defined standards that are possible without faith in Jesus. Professionalism is not supernatural. The heart of ministry is” (Preface, x).

Piper quickly concedes, “Ministry is professional in those areas of competency where the life of faith and the life of unbelief overlap.” But he contends that this area of overlap is not central to the ministry, but marginal. And he warns, “The pursuit of professionalism will push the supernatural center more and more into the corner while ministry becomes a set of secular competencies with a religious veneer” (Preface, x).

In the first chapter of the book, Piper expands on this thesis when he prays, “Banish professionalism from our midst, Oh God, and in its place put passionate prayer, poverty of spirit, hunger for God, rigorous study of holy things, white-hot devotion to Jesus Christ, utter indifference to all material gain, and unremitting labor to rescue the perishing, perfect the saints, and glorify our Sovereign Lord” (4).

For this reader, the preface and the first chapter were the best part of the book. The book includes 35 more chapters, each addressed to “Brothers.” The book, intentionally, reads like a prolonged letter of encouragement to younger pastors and pastors-in-training. Lutheran readers will appreciate the dozen or so references to Martin Luther, including some extended quotes from Luther’s writings.

In Chapter 15, “Brothers, Bitzer Was a Banker,” Piper encourages pastors to learn Hebrew and Greek and to keep on studying the Bible in the original languages. Piper notes that in some circles pastors who carry their Greek New Testaments to conferences are greeted with one-liners (102). The author contends, however, that when pastors are unable to study the Bible in the original languages “confidence…to determine the precise meaning of biblical texts diminishes. And with the confidence to interpret rigorously goes the confidence to preach powerfully” (99). Later, Piper asserts, “Weakness in Greek and Hebrew also gives rise to exegetical imprecision. And exegetical imprecision is the mother of liberal theology” (100). The title of the chapter refers to the fact that Heinrich Bitzer, the editor of Light on the Path, a book of daily Scripture readings in Hebrew and Greek, was a banker, i.e., a layman. “Brothers, must we be admonished by the sheep as to what our responsibility is as shepherds?” Piper asks (99).

Brothers, We Are Not Professionals also includes chapters which encourage pastors to pray, to be good stewards of their bodies, and to love their wives. It may seem that such admonitions would be redundant for men who have been called to teach others what God’s Word says, but we know the sin and hypocrisy that lurks in our hearts, so it’s valuable to hear the reminders from another pastor who has seen the problem and is concerned. I also found especially interesting the chapter titled, “Brothers, Show Your People Why God Inspired Hard Texts.”

Some chapters in the book, however, are not just unhelpful but actually contain false teaching. The title of Chapter 23, “Brothers, Magnify the Meaning of Baptism,” may sound promising, but the author proceeds to deprive baptism of its true meaning. Taking on 1 Peter 3:21, a passage which he concedes “frightens many Baptists away,” he all but ignores the phrase, “baptism that now saves you.” Instead he focuses on the final part of the verse to conclude, “Baptism is the outward appeal of faith to God in the heart” (158). In the chapter, “Brothers, God Loves His Glory,” Piper’s theological emphasis as a Baptist comes through when he repeatedly makes statements, such as, “Let us declare boldly and powerfully what God loves most—the glory of God” (9). The same is true when the author writes, “Superficial appearances to the contrary, this does not imply that true saints can lose their salvation” (128). In addition, Piper makes a statement that has the potential to damage souls with its confusion of law and gospel when he writes, “The only true sorrow for not having holiness comes from a love for holiness, not just from a fear of the consequences of not having it” (141).

Some years ago, Brothers, We Are Not Professionals was rated by Preaching magazine as one of the “Ten Best Books Every Preacher Should Read.” Given the number of doctrinal concerns with the book, it would be difficult to recommend it in good conscience. After the preface and the first chapter, the author did not continue to connect the dangers of “professionalism” with the subjects addressed in each chapter. In addition, the meaning of the phrase used in the subtitle, “radical ministry,” is one the reader would have to understand by inference rather than by a direct statement of what the author means with it. The book, however, does offer some good insight into the ministry priorities of one of this country’s most well-known Evangelical leaders—and along the way he says some things with which I’d strongly agree.

John Piper is founder and teacher of desiringGod.org and chancellor of Bethlehem College and Seminary in Minneapolis. For 33 years, he served as pastor of Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis.