Jump to:

Exegetical Theology: Proclaiming Life with 1 John – Part One

A series of readings from 1 John blankets the Sundays of Easter from Easter 2 to Easter 7. 1 John is a perfect match for our devotional lives as we proclaim the profound impact of eternal life in Christ upon us.

How does John write to us in a way befitting the Easter pulpit? How does he go about his task of anchoring Christians’ daily lives in resurrection hope and life? Asking and answering “how” questions like these is the nature of exegesis. Over the next three months, we’ll explore a sampling of answers together.

Left-Dislocation

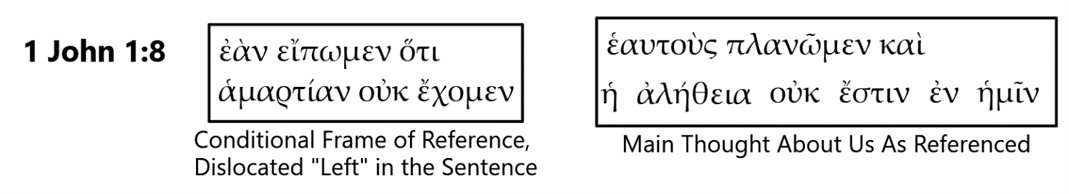

Left-dislocation is a reference to the way a writer might introduce a participant to us with an extended clause before making a comment about that participant in the main clause. For example, consider the use of ἐὰν + subjunctive verbs in left-dislocated clauses of 1 John 1:6-10 to introduce the kind of participant he wants us to consider, so he can then make a comment about such a one. The comment in the main clause holds the emphasis.

Though starting a condition with the protasis first – at the “left” – is the norm, John could have written the reverse: “We deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us if we say we have no sin.” But by introducing the participant first, he withholds judgment for a forceful finish. John often introduces a hypothetical person or version of “we” in this epistle using left-dislocation with a subjective participle or generic pronoun.

Why say it that way? John is introducing characteristics that are more or less observable and available to us – like saying or thinking we have no sin – in order to link that characteristic to a hidden, spiritual comment. He pointedly tells us who is tied to what reality. He helps us move out of any indifferent or casual approach to deadly ways of thinking or living by recharacterizing them in the main clause according to a real, though hidden, identity. Here in 1:8, it’s a negative identity that lacks the truth.

Antithesis

Antithesis is recognized from the way a writer uses parallel phrases, but with some alteration that creates a contrast. In 1 John 1:8-10, all three conditional clauses introduce us to ourselves as people speaking about sin, yet in two opposite ways (A/B below):

1:8 (A) If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves…

1:9 (B) If we confess our sins, God is faithful and just…

1:10 (A) If we claim we have not sinned, we make him out to be a liar…

Through such antitheses, John casts a binary view of each topic, like a coin with two sides. Antitheses drive the reader out of uncertainty’s fog to be able to distinguish truth from falsehood, life from death. Our persistent attitudes or behaviors are either in-line or out-of-line with God. This not only keeps things simple for the Christian, but also serves to reinforce our grip on Christ. We learn from John how to take hold of that for which Christ took hold of us. At the same time, through antithesis, John won’t let us miss the peril of the alternative, like “calling him [God] a liar.”

Do you hear that? Speech that is certain and clear from all sides. The sun has dawned. Light lives. Darkness is dead. “Christ is risen!” A perfect match.

Rev. Daniel Bondow serves at Living Savior, Littleton, CO.

Systematic Theology: Differences in the Words of Institution

Every year, teaching the section of catechism class on the Lord’s Supper, it hits me again how for something that is as big a deal in the life of the Christian as the sacrament is, we have surprisingly few Scriptures to compare. Luther reminds us that when it comes to what the sacrament is and ought to be, we have Matthew, Mark, Luke, and the Apostle Paul’s words to the Corinthians. Here’s where it gets interesting. They all say the same thing, but no two records of the words of institution are exactly alike.

As is often the case, when we find apparent inconsistencies in parallel passages, we might be troubled at first. When you’re used to sound bites and everything on video, you can very easily rewind, playback, and copy the dictation word by word. As we work through the comparison though, perhaps it helps to keep a couple of things in mind…

- Even the Greek is almost undoubtedly a translation. What language would Jesus have spoken with his disciples during the Passover meal? Most likely some combination of Hebrew and Aramaic, as they recited the Hebrew Scriptures, sang the Psalms, and conversed in their native tongue. Might Jesus have referred to the Septuagint? As their seminary professor, Jesus certainly could have. I still submit that Jesus was most likely not speaking Greek as he consecrated and distributed the elements.

- We rightly assume divine verbal inspiration of all four versions. What would be the Spirit’s purpose in capturing and communicating Jesus’ words differently? Could it be that he wanted to avoid their misuse? In other words, perhaps each writer was inspired to record the institution of the Supper in unique, yet equally valid wording, lest they be seen as a syllabic incantation rather than a gospel proclamation. (Here’s where one might do some research on the history of the expression “hocus pocus…”)

- The variation is good news for those of us who have the privilege and responsibility of distributing the Supper in our time and place. Though we make it our goal to “get it right” every time, depending on our past or current mode of distribution, depending on the hymnal or liturgy we are employing, and sadly, depending on the connection between our brains and our mouths –or momentary lack thereof, surely we have all mixed up words or confused versions so that we didn’t say exactly what we were supposed to or exactly what was printed before the people. Did Jesus repeat the words as each of the eleven received his body and blood for the very first time? Did he say the exact same words the same way to each? Ultimately, we don’t know. Luke and Paul weren’t there that night, and Mark is a definite maybe.

We might be thinking too deeply about what we’ll never fully grasp anyway. What we do know for sure is that by God’s rich grace, when we receive and distribute the Supper, Jesus’ words come through in our language. His body and blood commune with us no less than those who were there on the night he was betrayed. We celebrate the unity and partnership we’ve been given as his disciples, and we share in the forgiveness he promises.

Matthew

26 While they were eating, Jesus took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat; this is my body.”

27 Then he took the cup, gave thanks and offered it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you. 28 This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. 29 I tell you, I will not drink of this fruit of the vine from now on until that day when I drink it anew with you in my Father’s kingdom.”

Mark

22 While they were eating, Jesus took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take it; this is my body.”

23 Then he took the cup, gave thanks and offered it to them, and they all drank from it.

24 “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many,” he said to them.

Luke

19 And he took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me.”

20 In the same way, after the supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you.

1 Corinthians

For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, 24 and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me.” 25 In the same way, after supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me.”

Rev. Eric Schroeder serves at St. John’s in Wauwatosa, WI.

Historical Theology: Luther’s Spring 1521 Part 1: The Diet of Worms

Easter this year was a celebration filled with pent-up emotion. Thrills of thanksgiving echoed from most churches once again, a year after the massive shutdowns which profoundly affected our Holy Week and Easter observances last year. At the same time, perhaps a solemn patina covered the day, as we are struck by God’s gracious providential care, by which He has brought us through the current pandemic thus far, and to which we appeal for His continued blessing.

Five hundred years ago, on March 31, 1521, airs of emotion marked the celebration of Easter. In the Philippines, Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan and crew, having arrived there only days prior, celebrated the first documented Catholic Mass in the Philippines. No doubt a day of rejoicing! While half a world away, in Electoral Saxony, German theologian Martin Luther celebrated Easter with a distinct gravitas. He was about to embark on a journey of his own with a very uncertain outcome.[1]

Only a week later, while in transit and after preaching at Erfurt, Luther is said to have remarked, “I have had my Palm Sunday. I wonder whether this pomp is merely a temptation or whether it is also the sign of my impending passion.”[2] Championed though he was by the masses on the way, he headed to the imperial diet at Worms and a very uncertain outcome.

In a sense, of course, the outcome was already clear. Having issued Exsurge Domine the previous June, the matter was settled with Rome: Luther was expected to recant. Luther’s response to the bull was a clear condemnation of the papacy. Therefore, the formal bull of excommunication was already in the works. The only uncertainty was regarding the involvement of the state.

The Imperial Diet at Worms had been scheduled already in late 1520 and officially convened on January 28, 1521 to address several issues plaguing Emperor Charles V. Luther’s elector, Frederick the Wise, held the stance that Luther should not be condemned without a hearing. So, the influential elector used this as an opportunity to gain Luther a hearing. Indeed, this is what Luther himself wanted, and Charles reluctantly gave in. Over the intervening months, the offer was both rescinded and reissued, but finally the matter was settled: Luther was given an imperial guarantee of safe-passage and summoned to appear at Worms.

What follows is a familiar account to us. On April 16, 1521, Luther and his small party reached their destination with much fanfare and crowds in the thousands who had turned out to see him. But it was the gathering that awaited him the following day that was most important. On April 17, 1521 Luther was led into the Diet at about 4 PM. The hall was filled with all the politically powerful of Germany. Opposite him were the representatives of Rome. And in front of him was a table – piled high with his books.

Luther and the Elector had hoped this meeting would be a fair hearing. The Catholic cohort had insisted that this was all unnecessary. Ecclesiastical matters should be handled by the church. It all boiled down to two simple questions: Had he written these books? Was there a part of them he would now choose to recant?

The answer to the first question was simple. Yes, Luther acknowledged his authorship of the books presented. The answer to the second bore far more weight. Luther asked for time to consider if he would recant the [purported] heresies in them. “This touches God and his Word. This affects the salvation of souls. Of this Christ said, ‘He who denies me before men, him will I deny before my father.’ To say too little or too much would be dangerous. I beg you, give me time to think it over.”[3] Grudgingly, Luther was granted 24 hours. Overnight, Luther was encouraged by his companions to remain faithful to God and His Word.

Due to a slight delay, it was not until 6 PM the next day, April 18, 1521, that Luther was led into the presence of the emperor. He was again asked if he would recant. There could be no stalling now. Luther responded with a careful and conscientious answer regarding his works. They were not all the same kind. However, he appealed to Scripture as the standard by which all of them should be judged. If by that standard he would be shown to have erred, he would recant. “Once I have been taught, I shall be quite ready to renounce every error, and I shall be the first to cast my books into the fire.”[4]

This response was not acceptable to his examiner. Pressed for a more explicit statement, Luther famously replied, “Since then your serene majesty and your lordships seek a simple answer, I will give it in this manner, neither horned nor toothed: Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.”

“I cannot do otherwise, here I stand, may God help me, Amen.”[5]

Interestingly, it is unclear if the most memorable phrase, words that have become emblematic of Luther and the Reformation, ‘I cannot do otherwise, here I stand,’ were actually spoken. They were included in the earliest printed version of his statement, but were not recorded on the spot.[6] Nevertheless, the sentiment was clear. The hall erupted. Luther’s friends were overjoyed. Spanish soldiers shouted, “to the fire with him!” And Luther left the hall, raising his arms in victory once outside.[7]

Over the next several days, Luther met with a delegation led by the archbishop of Trier who continued to try to persuade him to recant. He did not, and on April 25, he requested to leave for Wittenberg.

The story of Luther’s spring 1521 does not end there. But, before we go on, we pause to both give thanks and take courage. In the moment of trial, Luther would stand with his conscience and the Word of God. He was both humble and honest. Even if not in the presence of royalty, in our day, too, we are called on to give careful and conscientious confession of the truth. May the Spirit so equip and embolden us to confess him before the world.

This year we mark the 500th anniversary of Luther’s confession at Worms. The date falls on the 3rd Sunday of Easter. Perhaps we would do well to bring before God’s people a remembrance of this event on that date – more, the call to stand faithfully with the truth, thankful for God’s gracious care for weak sinners and bold to confess His saving name despite all earthly uncertainty for it.

Rev. Matthew Kiecker serves at St. John’s in Lomira, WI.

[1] See: LW, 32, 101-131. For a thorough presentation of the account, see: James M Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House), 157-161.

[2] Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 179.

[3] Ibid., p. 183

[4] Luther, M. (1999). Luther’s works, vol. 32: Career of the Reformer II. (J. J. Pelikan, H. C. Oswald, & H. T. Lehmann, Eds.) (Vol. 32, p. 111). Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

[5] LW 32, pp. 112–113.

[6] Bainton, p. 185

[7] E.G. Schwiebert, Luther and His Times: The Reformation from a New Perspective (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1950), 505

Practical Theology: Greco-Roman Rhetoric for Preachers: Logos

In his Rhetoric (1.b.3), Aristotle distinguishes three rhetorical proofs: logos, pathos, and ethos. Logos is the most straight-forward. It refers to the content of the message, specifically the arguments that support its logical presentation. Aristotle defines it as persuasion “produced by the speech itself, in so far as it proves or seems to prove.” While he goes on at length to discuss various sub-categorizations, here we can focus on its application to preaching. Throughout this series, we’ll look at the biblical precedent in 1 Thessalonians and then note some applications.

Particularly Lutheran preachers may object that any consideration of logos seems to diminish the Holy Spirit’s role in preaching. However, in 1 Thessalonians 1:5, Paul certainly gives the Spirit a central role in powerful preaching, but he also is not denying the importance of words either. Consider further the background in Acts 17:2-4. Paul preached in the synagogue, where “he reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving to them that the Messiah had to suffer and rise from the dead.” Do our sermons look like that?

Here are two applications as preachers today consider logos:

- It is almost impossible for God’s Word to move a congregation if they leave confused. Any bit of unclarity or uncertainty in the preacher’s mind is going to be greatly compounded in the congregation’s mind. For that reason, when you prepare, I’d encourage you not to forgo composing a propositional and purpose statement or formally outlining your sermon. It’s the hardest part, but it’s difficult to have a well-organized (and well-understood) sermon if it is not outlined ahead of time.

- I now actually write longer sermons (about 2100 words). Once I went back to school and had to again submit sermons for critique, I realized how cursory my exposition was at times. Now I am more willing to delve into exegetical questions in sermonic exposition (here’s a recent example, highlights). This can, of course, be overdone, and it will depend on your demographic setting (it fits in mine). This preaching gives exposition a certain depth and trains your members how to “prove Christ from the Scriptures” as Paul did. For those worried about time, I have compensated by improving the smoothness of my delivery, so that the overall time (20 minutes) is not much different.

Resources:

- For those who have Bryan Chapell’s Christ-Centered Preaching, review the section “The Effectiveness of Testimony” on p. 34-41, the basis for my focus on 1 Thessalonians.

- The methodological validity of using Greco-Roman rhetoric is highly debated. For my case for a functional approach, see my upcoming WLQ review of Duane Litfin’s book, Paul’s Theology of Preaching: The Apostle’s Challenge to the Art of Persuasion in Ancient Corinth.

Rev. Jacob Haag is pastor at Redeemer Lutheran Church in Ann Arbor, MI, and a member of the Michigan District Commission on Worship.